One may say that the introduction is the most important and the most difficult-to-write part of the essay, because it defines the initial impression of the reader. However, without a proper body your essay won’t be worth much. So, how one is supposed to organize paragraphs in essay body?

One may say that the introduction is the most important and the most difficult-to-write part of the essay, because it defines the initial impression of the reader. However, without a proper body your essay won’t be worth much. So, how one is supposed to organize paragraphs in essay body?

The essay structure is pretty closely tied up with the contents, which simultaneously makes your job easier and harder. It’s easier because each paragraph is supposed to have more or less the same general structure, which means no agony of choosing. Yet it’s harder because you are very limited in terms of how you are supposed to elaborate on the topics you’ve chosen.

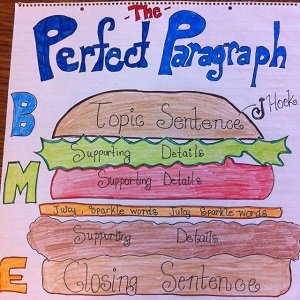

Each main idea of your essay should be singled out into a separate paragraph – the most common school essay structure, aptly named a five-paragraph essay, contains three main ideas, each represented with a single paragraph, and a paragraph apiece for introduction and conclusion.

However, stating the main idea is not enough; in addition to that, each paragraph should contain at least two or three supporting ideas.

In the long run, it means that when writing an essay you will be more or less safe if you do it on a step-by-step basis. First, single out all main ideas your point rests on. Then, define the ideas that will be best to support them. After that, use three or four lines apiece to flesh them out.

Finally, if you wish (and if you haven’t yet reached your word limit, don’t forget to leave some space for introduction and conclusion), you may write a concluding or summarizing sentence after each paragraph. However, in most cases you are not advised to do so – you can hardly expect your reader to forget what he/she read three seconds ago, and points made in an average school/college essay are usually simple enough to make such summaries redundant. In addition to that, they almost universally sound incredibly forced and make the reader immediately suspect you of including them for the sole purpose of bloating the word count.

As you may see, the essay’s structure is quite rigid – and it is for the best, really. By following the aforementioned principles to the letter one learns to steer clear of all the ideas that don’t immediately promote the main point of the essay. Each sentence and each paragraph should fulfill its role; there is no place for freeloaders. Even if you see an idea that is kind of connected with the main topic and you are dying to include it, if for nothing else but to show off your knowledge, it may be better to avoid it. If it doesn’t directly support your point and develop your topic, it is taking you off track.

In the long run, the rigidness of the essay as a written form is a blessing in disguise – like most limitations, it not so much stifles creativity as promotes it.